Rethinking CEX Listings, Onchain Liquidity, and What “Market Making” Really Means

For years, the default path was simple: launch a token, chase centralized exchange listings, hire a market maker (or don’t), hope it all works out. That path still exists but is it aligned with what token projects actually need?

Should token projects be their own onchain market maker?

It’s a question that has been making its way into more and more conversations, so I invited Primal Glenn (BD at Bancor) and Dr. Mark Richardson (Project Lead at Bancor) to join me on a Blockchain Banter dedicated to the topic.

We walked through a real example, complete with what makes it difficult for projects to make a market on traditional and concentrated liquidity AMMs, and explored what a better, transparent onchain setup can look like.

The CEX listing problem no one wants to talk about

Glenn opened with a concrete case.

A new project — no token live yet, but with a token central to its protocol — was recently preparing for its TGE (token generation event). As part of the launch, they approached centralized exchanges.

What they were told by one in particular is something many founders have quietly heard:

The exchange wanted 8–10% of the total token supply.

On top of that, there were listing fees.

And beyond that exist expected market-making arrangements — either direct retainers or token loans to third-party market makers.

“From day one, that’s a huge chunk of supply and capital out the door.” And this isn’t just about getting a listing; it’s about funding ongoing market quality on those venues.

Mark added nuance: in many “traditional” setups, it’s usually the market maker — not the exchange — that receives a large token allocation, under a contract that aligns incentives and defines how those tokens can be used.

In crypto, the lines are blurry:

Many centralized exchanges effectively act as both the venue and the dominant market maker.

Some ask for token allocations that are then distributed to their own token holders via launchpads, quests, or staking programs.

Projects can find themselves paying fees and handing over supply for programs that mostly benefit the exchange’s own ecosystem, not their own respective community.

Mark summarized it bluntly: some of these deals are “par for the course, but maybe a little more predatory than neutral.”

In this particular case, the project decided to walk away, though not without exposing the supposed predatory tactics of the centralized exchange first.

Onchain launches and the transparency trap

The project chose to skip the CEX route and conduct its TGE onchain using a standard constant product AMM. On paper, that sounds more transparent and fair.

In practice, it raised a different problem.

Onchain observers watched as the project was selling into the pool, a unilateral sell pressure.

The Crypto Twitter community was quick to respond, saying that if they were trying to “market make,” — like they claimed — users expect to see:

Both selling and buying, not just selling.

Some kind of visible structure to the strategy.

The project might have had a plan but the mechanics weren’t obvious. And without a clear explanation, it appeared as though the team was simply dumping on the market.

If projects do want to be their own market maker onchain, what tools do they actually have and how can the mechanics be obvious to onlookers?

Why traditional AMMs don’t fit what projects need

To understand the constraints, Mark went back to basics.

The earliest Bancor pools used the classic constant product AMM:

If a project wants to seed a pool with, say, $50,000 worth of its token and $50,000 of USDC, it looks respectable. Market cap can be inferred, the pool looks deep, and a market exists.

But at launch, almost no one outside the project holds the token.

That means:

If no one holds the token yet, no one can sell into the pool.

The initial USDC is largely symbolic — effectively untouchable until someone buys the token.

On top of that, the project is forced to lock up meaningful amounts of quote assets (USDC, ETH, etc.) in a structure that doesn’t reflect how a project actually thinks about its token:

It wants to sell a token supply at chosen prices, not just “from 0 to infinity.”

It wants to transparently buy back at a lower price, not where it just sold.

It wants to fund operations and manage runway using those proceeds.

Constant product AMMs weren’t designed with this use case in mind. They were designed to create continuous, permissionless liquidity — not to effectively, strategically make a market.

At Zebu Live, Bancor Co-founder Eyal Hertzog discusses how automated market makers (AMMs) reshaped finance — and why the next generation must go beyond simplicity. Traditional market makers needed more sophistication, strategy, and control. That need inspired the creation of Carbon DeFi, Bancor’s next-generation DEX — designed for institutional-grade strategy execution and smarter liquidity management.

Concentrated liquidity: more control, still the wrong shape

Amplified liquidity, commonly known as concentrated liquidity, was meant to fix some of these inefficiencies.

Glenn pointed out that with concentrated liquidity:

A project can provide single-sided liquidity out of the money (for example, only its own token at a higher price than the current market).

It can decide, “I want to sell from this price upward, without having to seed both assets.”

That’s a step closer to what a token issuer might want.

But Mark highlighted a fundamental constraint: concentrated liquidity systems still follow the same underlying rule:

When your asks are taken, they are converted into bids behind the price you just traded at, minus a “fee”. I put this in quotation marks because Mark despises the term “fee” in DeFi. For more on that though, see his EthCC presentation “Fixing Objectively Bad Models in LP Performance Evaluations”

Put differently:

If a pool sells a token at a given price, it then automatically offers to buy it back at nearly the same price.

That might be fine for consumer-focused liquidity, but it’s not how a project or professional market maker typically manages risk.

You can sell millions worth of tokens, only to be forced to stand ready to buy them all back at almost the same price, for a tiny fee.

To make this behave more like a real market-making engine, you’d need:

Automation to withdraw liquidity at the right time.

Bots (keepers) to repost liquidity at new prices.

A constant battle for blockspace and gas against other onchain actors.

Additional third-party infrastructure and associated fees.

Glenn summed it up: if you try to run a true buy low, sell high strategy across multiple price levels using standard CLAMMs, you end up with a complicated, fragile bot stack, and you’re still constrained by the protocol’s structure.

What projects really want from onchain market making

From the founder’s perspective, the wish list is straightforward:

Sell tokens at defined price points or over a defined price range.

Buy back tokens at lower prices using proceeds, in a way that can run without bots or babysitting blocks.

Keep everything onchain and transparent, so the community can see the logic and structure.

Avoid opaque off-exchange deals, double-dipping listing terms, and misaligned incentives.

In other words:

“Let the project express its intended market structure directly onchain — without needing to wire half its supply to an exchange or maintain a fragile web of bots.”

That’s where Carbon DeFi entered the conversation.

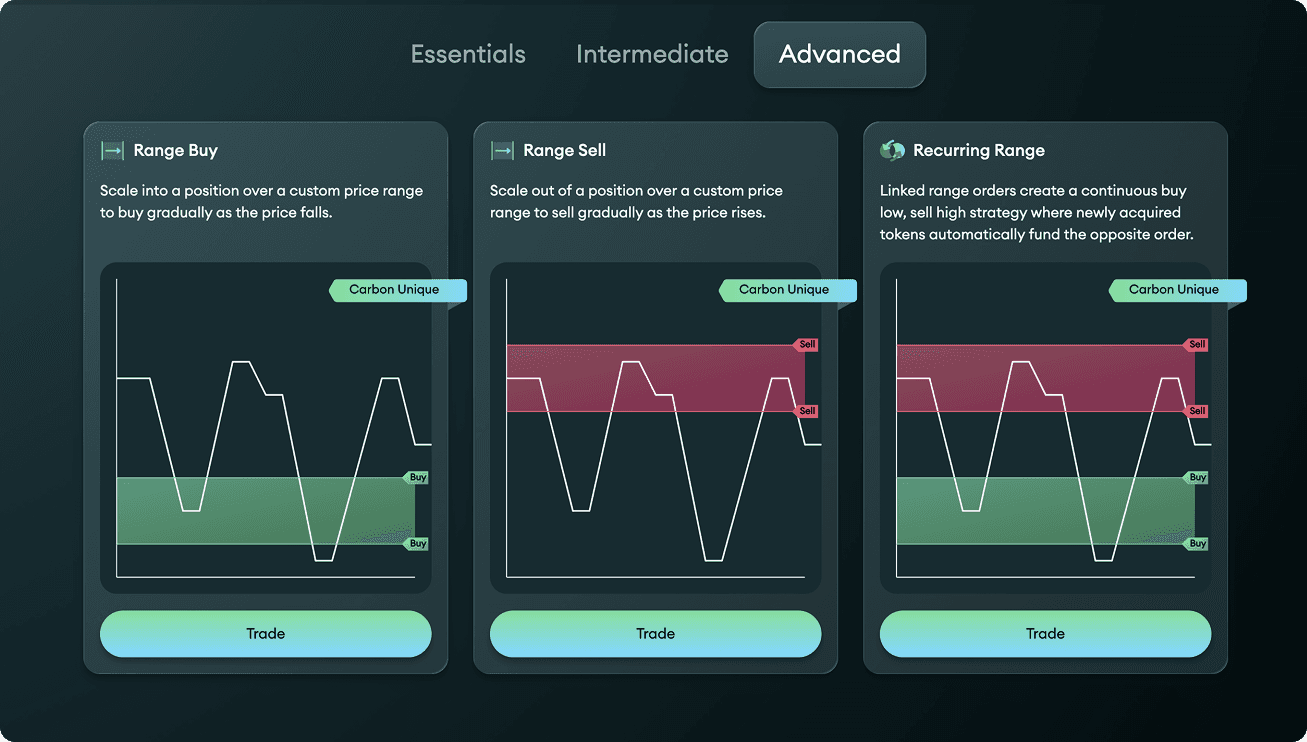

How Carbon DeFi turns token projects into onchain market makers

Glenn walked through how Carbon DeFi is being used by token projects today to build exactly the kind of structure this particular project was missing.

At a high level, Carbon DeFi lets a token project:

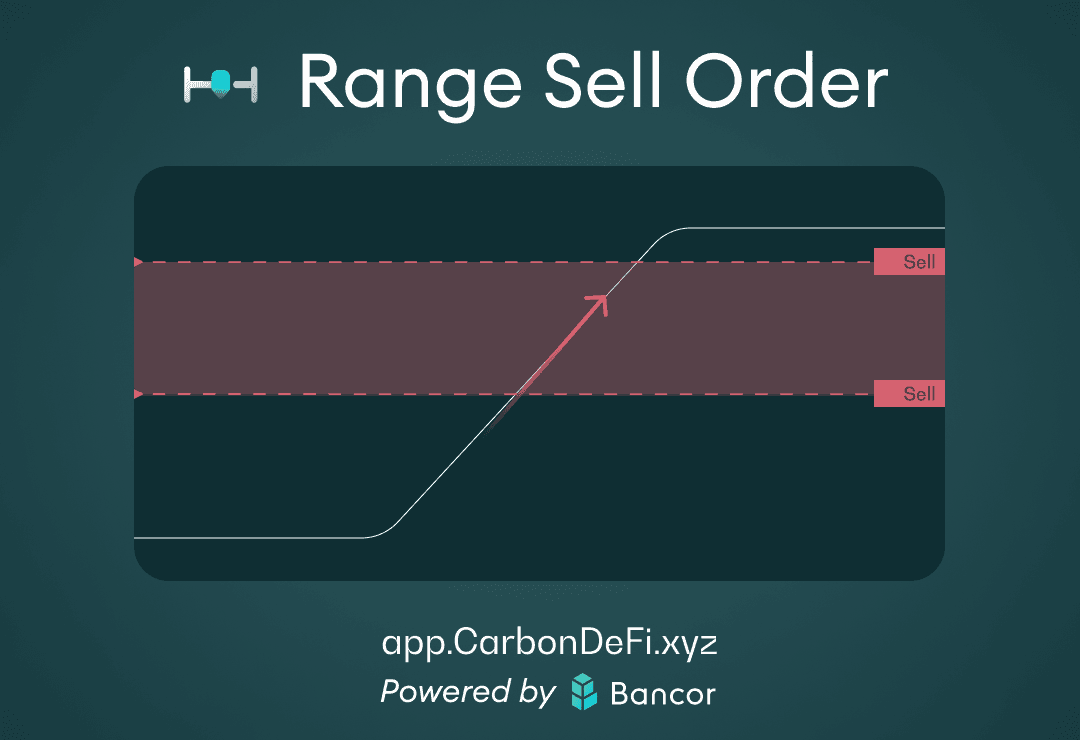

1. Define a sell order

Single-sided if desired (for example, only the project’s token).

Either at a specific price or across a range (e.g., sell from $0.37 up to $0.50).

All onchain, visible to anyone.

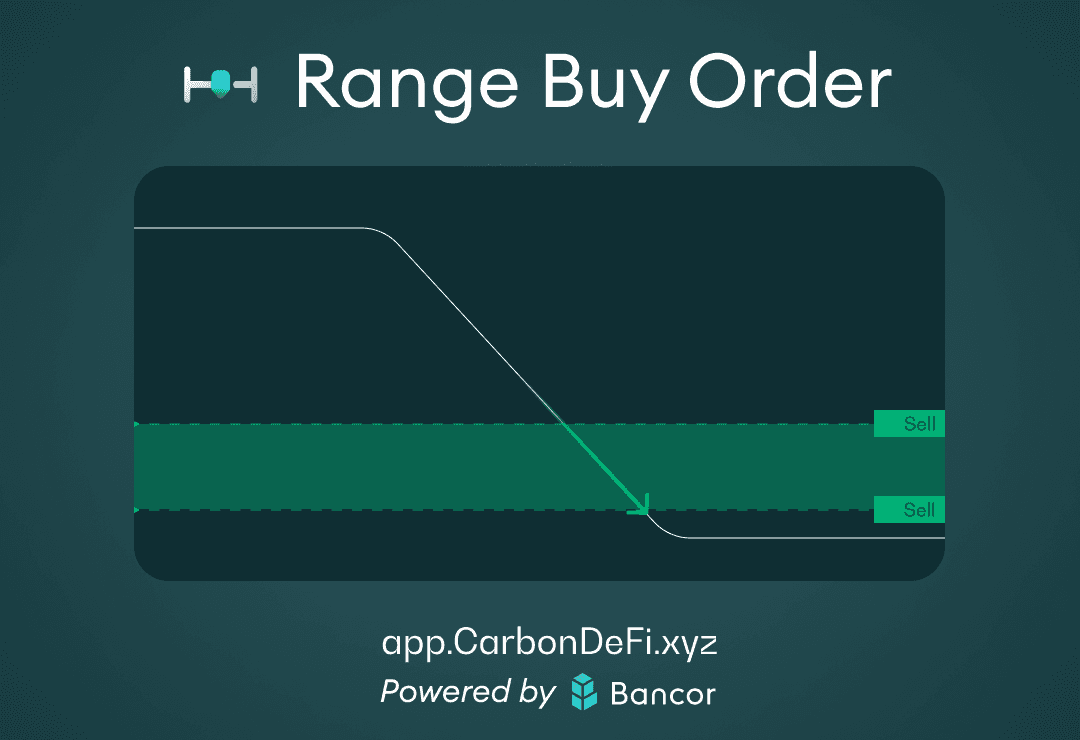

2. Define a buy order at a different price

Buy back the token at a lower price or range using the proceeds from the sell order.

This buy order is linked to the sell order, but not constrained to the same price level like a typical CLAMM.

3. Recycle proceeds automatically

When the sell side executes, the token received is automatically rotated into the buy order.

When the buy side executes, the purchased tokens rotate back to the sell side.

The result is a recurring, “buy low, sell high, repeat” loop, entirely onchain.

Crucially:

The project can fund only one side initially (for example, just its own token) and let proceeds fund the other side.

It can adjust ranges, prices, funding, and strategy type at any time without tearing down and rebuilding everything.

Every strategy is fully transparent:

Orders live onchain.

The Carbon DeFi UI can display strategies, fills, edits, and timestamps.

Projects can share direct strategy links with their communities.

This addresses exactly the criticisms that hit the project in Glenn’s example:

Instead of a wallet that “just sells,” viewers can see a structured sell range and a corresponding buy range.

Instead of trying to infer intent from random transactions, users can see the intended market logic encoded as a strategy.

As Glenn put it, this isn’t about outsourcing everything to an external market maker; it’s about giving token projects a native, protocol-level way to structure their own markets onchain — without bots, keepers, or offchain contracts.

So, should token projects be their own onchain market maker?

By the end of the conversation, the answer wasn’t a simple yes or no.

On centralized exchanges, “being your own market maker” is often unrealistic. The platform, the listing terms, and the market-making relationships are tightly coupled, and small projects are rarely in control.

Onchain, it’s different.

If a token project:

Controls its supply,

Has a clear idea of how it wants to distribute and recycle that supply, and

Uses tooling that lets it express real market logic directly onchain,

then yes — being its own onchain market maker can not only be viable, but preferable.

As Mark noted:

A project that controls its own token supply is not bound by the same constraints as a third-party market maker that has to operate purely for profit. It can define success differently: distribution, stability, runway, community alignment.

What matters is having infrastructure that respects that reality. For many teams, that’s starting to look less like a centralized listing negotiation — and more like building transparent, programmable onchain markets with systems like Carbon DeFi.

Full Recording

https://x.com/i/broadcasts/1BdxYZdVwrzKX

Blockchain Banter

Blockchain Banter is a live, unscripted discussion series where industry experts, builders, and thought leaders come together to share knowledge, challenge ideas, and explore the evolving landscape of DeFi and blockchain.

Presented by Bancor

Bancor has always been at the forefront of DeFi innovation, beginning in 2016 with the invention of the Constant Product Automated Market Maker and “pool tokens” — which still remain extensively used across the industry. The newest inventions powering Carbon DeFi and Arb Fast Lane substantiate Bancor’s deep commitment to delivering excellence, advancing the industry, and pushing the boundaries of what is possible in the world of decentralized finance. For more information, please visit www.bancor.network.